Learn how to build a versatile, multi-purpose “extra room” in your backyard.

Our editors and experts handpick every product we feature. We may earn a commission from your purchases.Learn more.

Learn how to build a versatile, multi-purpose “extra room” in your backyard.

Our editors and experts handpick every product we feature. We may earn a commission from your purchases.Learn more.

4 to 6 weeks.

Advanced

Around $25000

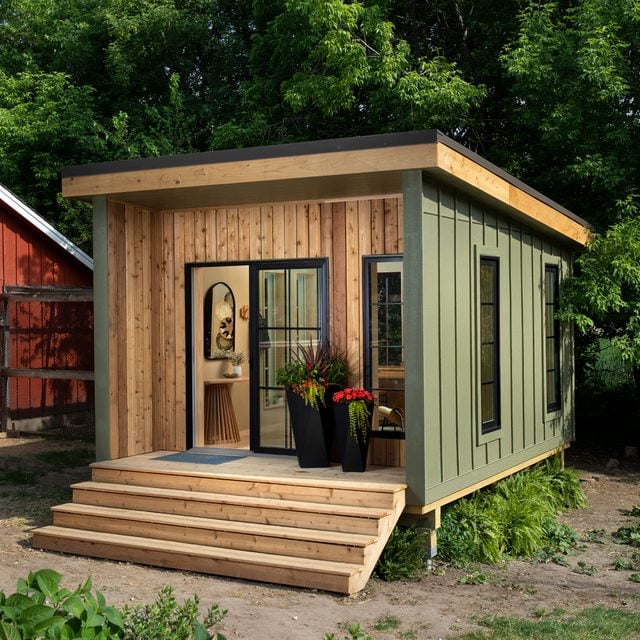

In this project, we'll explore several sustainable building materials and practices, creating a backyard building that fits nearly any need.

The inspiration for our backyard build stemmed from two ideas. First, we wanted to showcase some sustainable building materials and practices. Second was the transition to a “work-from-home” lifestyle that many folks started over the last few years, creating a need for home office space.

But this type of backyard building could suit many purposes. You could use it as a kids play room, a music or art studio, or just a place to hang out outside of your home.

Our building doesn’t have plumbing, only electricity, which greatly simplified the build and kept the cost down. Because of the small space and excellent insulation, you could probably heat it with an incandescent light bulb.

While you’re at it, also learn about sustainable architecture, the eco-friendly construction way.

When it came time to break ground on our build, the ground on our site was way too wet to pour a concrete slab. Even accessing the site with a concrete truck would have been a big challenge. So we changed plans and went with helical piers for our foundation.

This proved a plus in several ways. First, we didn’t disturb the ground at all, a great call on this little wetland area. Second, we didn’t need to wait for concrete to cure before we started building. As soon as the piers were in, we were off and running.

Lastly, this method saved us a lot of work. Besides no site excavation, we avoided building a form, hauling wheelbarrows full of concrete or finishing the concrete. We may never pour a slab again!

By going with helical piers instead of a concrete slab, our site required no preparation other than laying out the locations of the piers. The pros from Structural Pier Tech calculated the number and spacing of the piers we needed — three at the front and three at the back, spaced evenly.

Helical piers are sort of like seven-foot-long screws. Using special equipment, our contractor drove the piers into the ground until they reached a specific torque. If the necessary torque isn’t achieved from one length of pier, they’ll attach another section. Two of our piers required a depth of 21 feet!

The driven piers didn’t end up level with each other. So we located the highest pier and used that as our starting point.

We used treated 6×6 posts on top of each pier, cut to the proper height to make a level bearing for our two beams. Then we attached them with steel brackets that connect to the tops of the piers.

We constructed our support beams by laminating three 2-by’s with nails and construction adhesive. We secured the beams to the tops of the posts with special post-beam connectors.

At this point, we’re on to standard deck framing. We cut the joists to length and arranged them on top of the beams, then added the front and back rim joists.

After squaring the deck assembly, we secured it to the beams with hurricane straps. We added blocking on top of the beams and at the front, where our deck would start. That way, we could insulate only the part of the floor that’s under the interior portion of the finished structure.

Since our floor is up off the ground, we needed to insulate it well to maintain interior temperature and prevent condensation. We attached a 2×2 cleat along the bottom edges of all the joists, then cut GoBoard – a foam-based, waterproof underlayment for tile – to fill each joist cavity.

On top of the GoBoard, we set in 1-1/2-in.-thick rigid foam board insulation and sealed around the edges with expanding foam. Next, we filled the joist cavities with mineral wool batts — a sustainable insulation derived from the biproducts of the steel and copper industry.

With the floor insulated, we installed the subfloor decking. For this, we used 3/4-inch tongue and groove Oriented Strand Board (OSB), fastened with nails and construction adhesive.

Once this part was done, we were vigilant about tarping the deck during the next steps until the structure had walls with sheathing and a roof. That protected our insulated floor from rain.

Building sustainably doesn’t always mean new and innovative building products. Sometimes it’s modifying a traditional building method to be more energy efficient. That’s exactly what we did when designing our framing.

We wanted to keep it simple and efficient, so we built double 2×4 walls. This framing technique adds space for lots of insulation and removes the heat transfer that happens when individual studs are in contact with the inner and outer wall.

We began our double-wall construction by building the outer walls.

Start with a top and bottom plate cut to the length of the wall and mark out the 16-in on-center stud layout, as well as the window locations, with jack and king studs. On a standard roof with a ridge beam, the layout is marked on the top and bottom plate at the same time.

On this sloped, shed-style type of roof, we laid out the heights of the walls on the floor and transferred the layout to the angled top plate to get an accurate measurement for each stud.

Cut all the studs, including the jack, king and cripple studs, for the windows. Line them up with the layout marks and nail them through the plates. Tip up each wall as you build them, brace them plumb, and fasten them together at the corners.

Pro tip: When building a shed-style roof, save yourself time and write down the measurements for each stud so you don’t have to re-measure for the opposite side.

Once the exterior walls are up, cut a 2×4 bottom plate three inches shorter than the distance between the walls. Place it between the walls with a 2×4 spacer at the ends. Then copy the layout of the exterior walls onto the new bottom plate. Transfer the marks to the top plate, then cut the studs and build the wall.

We built the end walls first and tipped them up as they were built. We used a 2×4 spacer between the inner and outer walls to position them and nailed them through the bottom plate. We make sure we nailed them into the joist below whenever possible and not just the subfloor.

Transferring the stud layout from the outer to the inner wall makes it easy to match the window openings. But at the windows, not all the framing parts need to be transferred to the inner wall.

Since the outer wall bears the weight of the roof, it will contain any headers, jack and king studs, reducing the amount of framing material needed and maximizing the insulation space of the inner wall.

After installing the sheathing and roof, the final step to make these walls extra energy efficient is filling the stud spaces with insulation.

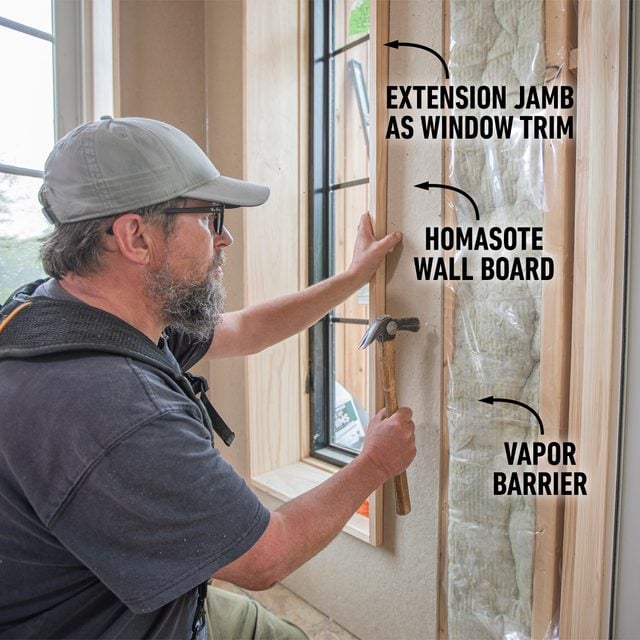

We started by filling the outer wall with mineral wool insulation, cutting the batts to fit the stud bays. Next, we ran our wiring, then added mineral wool batts to the inner wall. Lastly, we covered the wall with a vapor barrier before installing the wallboard.

With the walls framed, it was time to add the sheathing. We used Georgia Pacific ForceField sheathing that incorporates a moisture barrier. So no tacking a water-resistant house wrap after applying the sheathing, which was a real time saver. All we had to do was tape the seams.

We purchased engineered I-joists for our rafters. These I-joists are stiffer, straighter, and lighter weight than comparable 2-by material.

We placed the rafters and then attached a Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) beam to the front posts to support the three-foot overhang, and a 2×10 subfascia to the back to tie the roof framing together. We secured the I-beam rafters to the LVL beams with appropriately sized joist hangers.

Once the roof was framed, we applied the roof deck, using the same sheathing material we did on the walls. That was another time saver here, as there was no underlayment required. We simply taped the seams with a purpose-made heavier, more flexible tape than we used on the wall sheathing.

At this point, with no rain in the forecast, we moved on to installing the windows and siding before installing the metal roof panels.

To save some money and keep some perfectly good products out of the landfill, purchase windows from a re-use company that sells recycled building materials. Some were salvaged or mis-ordered. And some are new materials that, for one reason or another, were never used.

We lucked out and found new windows at a big discount. If these windows had been previously installed, we may have had to order some replacement parts from the manufacturer, like nailing flanges and hardware. Another common thing when you’re re-using windows: You might not find a matching set, so you’ll likely make some compromises.

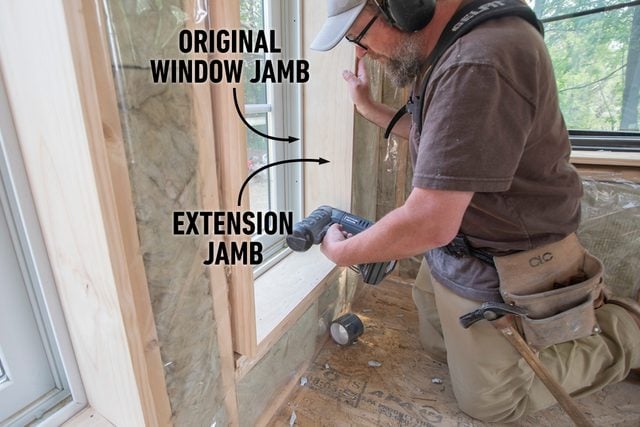

As was the case for us, you’ll also need to add extension jambs to the window to meet the depth of your framing. Since our wall framing was double-thick, our extension jambs were nearly eight inches deep, making for useful window sills. And we used the extension jambs themselves as the window trim.

Once you have all the necessary parts, installing previously used windows is no different than new windows.

In new construction, frame in the window openings as you’re framing the walls (See Step 14). To find the size of the openings, measure the windows and add 1-1/2-inches to the width and height. This leaves space on all sides to plumb and level using shims, as well as insulation.

If you’re installing your windows in existing construction, know that if your windows aren’t perfectly sized to your rough opening, you’ll have extra work both inside and out, adding framing and refinishing and trimming out wall surfaces.

Cut a piece of cedar bevel siding to fit the window sill. Set it in place with the thin edge towards the exterior. This way, if any moisture does get in around the window, it’ll flow outward.

Tape the sill using flexible flashing tape, extending about six inches up each side. Tape the seams where the sheathing meets the studs using flashing tape.

Level two pairs of shims across the sill and nail them in place. Apply silicone to the flange, then enlist a helper to tip the window into the opening. Set it on the sill shims and center it side-to-side.

With one person inside with a level and one outside with a hammer and roofing nails, it’s time to fasten the window to the framing.

Verify the sill is level and nail the two bottom corners of the flange. Then plumb the sides and nail the top corners. Use a straightedge on the jambs as you’re nailing off the flange, shimming the jambs as need to keep them perfectly straight.

Tape over the nailing flanges using window flashing tape. On the inside, add a few trim head screws – if possible – through the jambs into the studs to firmly secure the windows.

We pre-built extension jambs for our windows using pocket hole joinery instead of installing one board at a time. This approach ensures that the extension jamb is square, and it makes installation a breeze. Just set the assembled jamb in place and fasten it to the framing.

Siding covers all our homes, sheds, garages, and every other building you see. Whether it’s brick, wood, vinyl, steel, its all siding. It’s the first layer of protection our homes have from the elements.

Installing siding yourself is no easy task. But once you have a basic understanding of the different parts and how they go together, it’s a matter of making accurate cuts and following the manufacturer’s recommendations for fastening. We used an engineered wood siding from Sherwin-Williams to create this classic board and batten look.

We’re big fans of engineered wood siding. The boards are lightweight, always straight, tough, and can be ordered pre-finished with a special coating that comes with a 15-year or more fade warranty. It’s also made from wood chips from the wood processing industry, keeping it from the landfill. On top of that, it can be cut with regular saw blades. And it’s easy to install.

We fastened 1×6 trim at the bottom of the building, making sure it was level all the way around. This skirt trim gives the bottom of the siding a finished look and provides a ledge for the tall siding panels to rest while nailing them on.

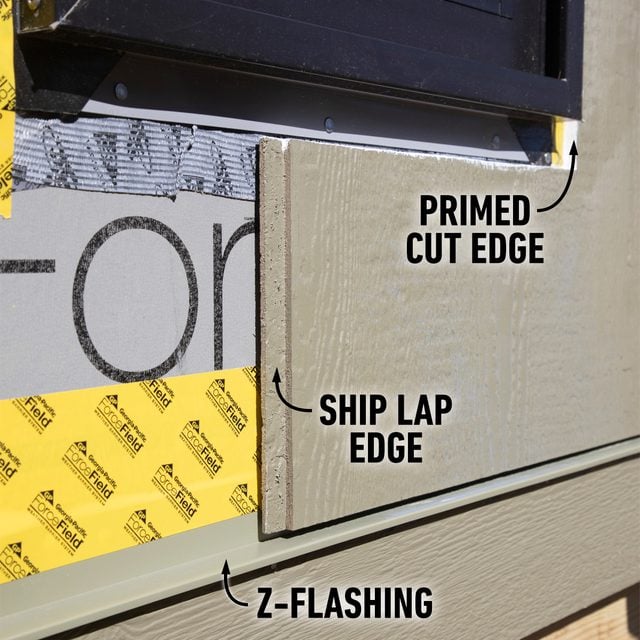

Fasten the skirt trim using two-inch siding nails. Then secure one-inch Z-flashing on the top edge of the trim to prevent standing water from wicking into the trim.

Pro tip: On the Z-flashing, mark all the studs that land every 16 inches on center, trimmers, cripples and headers to make fastening the siding less of a guessing game.

The siding panels have shiplap edges, so we started from one corner and worked across the walls, making sure the panel edge joints overlap the previous one.

After we cut each panel to length and width and the window cut-outs were made, we raised the panel 1/4-inch above the skirt trim, made sure it was plumb and fastened it to the studs. As you’re cutting panels, be sure to prime any raw edges to prevent moisture damage.

Since the windows are trimmed with 3-1/2-inch casing, we made the notches for the window about 1-1/2-inch larger. This allowed us plenty of wiggle room to position the panel AND avoid further buildup over the windows nail flange.

Note: On this project, our eight foot tall panels didn’t cover the entire wall, leaving us with with a horizontal seam. If left with no flashing, it would collect water and rot the siding. So we installed 3/8-inch Z-flashing on top of the seam to prevent water intrusion.

Engineered siding companies manufacture a special trim piece to make covering outside corners of buildings much easier. The corner trim comes pre-assembled so you can simply cut it to length and nail it on.

You could nail the window trim pieces up individually. We decided to pre-build the window casing using pocket hole joinery, then nail them on as one piece. This was faster and ensured the trim joints lined up perfectly.

To size the opening in the finished frame, start by cutting the bottom piece 3/8-inch longer than the windows width. The sides cover the ends of the bottom piece, and should extend up to a height that’s 3/8-inch taller than the window. The top piece attaches to the top ends of the side pieces. The length of the top is the full width of the assembled bottom.

The soffit is the underside of the roof overhang. There are special soffit panels made for this purpose, but we cut leftover siding panels to fit. Attach the soffit panels using two-inch siding nails.

Next, install the battens. Battens are decorative 1×2 trim pieces nailed on top of the siding panels to hide the seams. Cut the battens to fit vertically between the drip cap, window trim and soffit. Fasten them using siding nails, making sure they’re perfectly plumb.

Once the siding is up, the last step is sealing the windows to the trim with a color matched caulk. Only caulk the sides, though. If any moisture does get in, you want it to drain out at the bottom of the window, instead of getting trapped. Paint any exposed nail heads and touch up any other blemishes on the siding.

Aside from the teamwork required to get long metal roofing panels up the ladders, roofing a simple shed roof like this is about as easy as it gets. Including all the edge trim, we finished it up in a morning. When you’re working on a roof, be sure to use a safety harness.

Attach any electrical boxes you need for receptacle outlets, lighting or other wiring needs. While it would be simple with our double wall framing to run the cable in the space between the walls, we drilled holes in the inner wall, as in a typical installation. This makes securing the cable and knowing exactly where it is much easier.

All electrical work, including installation of a panel, by code must be performed by a licensed electrician and be inspected before applying any interior wall covering.

This step is shown in the final step of the framing process (See Step 15). Fill the wall cavities by cutting insulation batts to fit.

Here’s where our double wall framing method really pays dividends! We hired a spray foam contractor to insulate our ceiling. The main reason being, to reach the required R-value using batts, we would have needed a 16-inch thick roof system.

We installed a tongue and groove ceiling using pine V-groove siding, left natural without any finish.

Starting on the low side, set a board in place with the groove against the wall and the tongue towards the room. Face nail the wall edge of the board, then nail through the tongue at an angle to finish fastening, using 15-gauge finish nails. On the remaining boards, you’ll only need to nail through the tongue until you reach the final board.

Be sure to measure as you go to verify that you’ll come out with a straight board when you reach the high wall.

Before applying the wall covering, we assembled extension jambs for each window and fastened them to the framing. We made these jambs deep enough to stand proud of the wall covering, creating a no-work window trim.

We finished the interior with Homasote, a product with a fabric-like texture. Inside, it’s sort of like paper mache. It’s used widely for soundproofing underneath drywall.

We opted to leave the Homasote as the finished wall surface, letting the seams show. No mudding or painting needed, just carefully cutting around the window and door extension jambs. To finish up, we applied trim at the tops of the walls and applied a matching caulk in the corners.

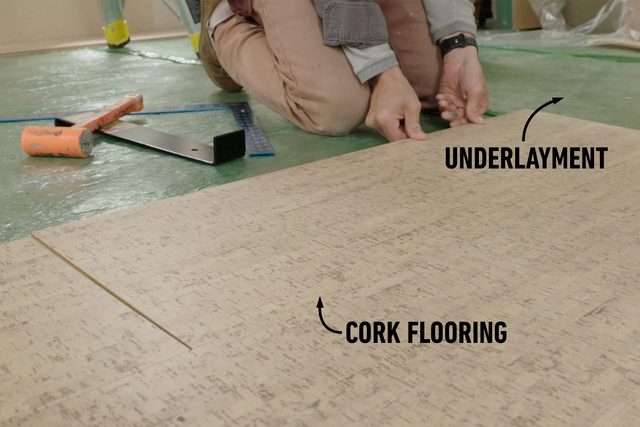

For our flooring, we installed a product from LL Flooring, called Castelo Cork Flooring, over their QuietWalk Max Underlayment. The flooring is essentially a “cork sandwich” with a medium density fiberboard (MDF) core. The cork veneer face features a protective clear coating.

Cork is a sustainable material with insulating properties that’s warm and quiet underfoot. Castelo Cork Flooring features a click-together installation, just like a laminate floor. It’s fast and easy to install, and we love the look!

After the flooring was down, we cut and installed a square-profile baseboard to complement the window jambs.

We clad the deck walls using 5/4 cedar decking.

Before applying the decking, we covered the walls with lightweight black landscaping fabric to hide any flashing tape that might show through the gaps in the decking boards. On top of the fabric, we tacked on 1/4-inch-thick furring strips at an angle to prevent water from getting trapped behind the decking boards.

To install the boards, we used the Camo hidden fastening system. This hides the fasteners by allowing you to drive the screws through the edge of the board at an angle.

We decided to run our stairs all the way across the deck.

First, we calculated where the stair stringers would hit the ground. Then we dug a trench and laid in a grade beam on top of gravel. This creates a strong foundation for the bottom ends of the stringers. We installed the deck boards aligned with the wall boards.

When the deck was finished, we sanded off any footprints and rolled out a temporary protective covering to prevent marring as we walked in and out to bring in furniture.

To finish up, we installed electrical outlets, a light switch and lights.

While these lights look like recessed can lights, they’re actually Feit Electric Ultra-Thin Canless LED lights. Each light comes with its own junction box to connect to the wiring.

These boxes have a switch that allows you to choose a color temperature. The lights are dimmable, and one function only illuminates the outer rim.